Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor

California Cactus Wrens. Photo: RAHamilton

A wildlife corridor allows animals and plants to move between habitat areas, which benefits wildlife for many reasons. Larger animals—like our grey fox, bobcat, and coyote—need space to hunt. In areas too small, their numbers fall, and they die out. Animals and birds must also move to find unrelated mates. To protect the health of Orange County wildlife and plants, our coast and foothills wildlands must be connected. The wildlife corridor will be habitat for smaller wildlife, and a vital pathway for larger ones.

The Laguna coast wilderness has been isolated from other wildlands for at least two decades. Federal biologists have found increasing rates of a debilitating disease in coastal bobcats that might signal genetic weakness. Cactus wren populations hard hit by the 1993 wildfires have become genetically different from their relatives in Orange County and San Diego. The remaining birds are inbreeding, and nestling survival rate is low.

The Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor is an audacious, cutting-edge endeavor, but it must succeed. The stakes for 22,000 acres of coastal wildlands are very high.

The Coast to Cleveland Connection

The Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor is a partially-completed linkage between Orange County’s coastal wilderness and the Santa Ana Mountains. It is envisioned as a wide, winding strip of native vegetation that roughly follows sections of San Diego, Serrano and Borrego Creeks. This 6-mile corridor will link the 22,000 acres of protected natural lands in the Laguna coast to the more than 150,000 acres of wilderness around the Santa Ana Mountains, including Cleveland National Forest, Whiting Ranch, and Limestone Canyon.

The Coast to Cleveland Connection

The Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor is a partially-completed linkage between Orange County’s coastal wilderness and the Santa Ana Mountains. It is envisioned as a wide, winding strip of native vegetation that roughly follows sections of San Diego, Serrano and Borrego Creeks. This 6-mile corridor will link the 22,000 acres of protected natural la

nds in the Laguna coast to the more than 150,000 acres of wilderness around the Santa Ana Mountains, including Cleveland National Forest, Whiting Ranch, and Limestone Canyon.

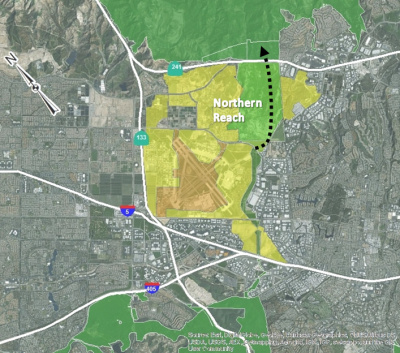

The map above shows the corridor’s general path, as well as various properties along it. Fringes of t

he corridor’s “destination” wilderness areas to the north and south are shown in green at the top and bottom of the map.

The corridor can be understood as three reaches, or segments:

Northern Reach: Shown in lighter green on the map, the properties north of Irvine Boulevard consist of the 900-acre El Toro Habitat Preserve on land managed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and a triangular County property containing the Alton wildlife movement corridor that connects under Irvine Blvd to the central reach.

Central Reach: The central reach of the corridor roughly follows the east side of the Great Park Neighborhoods and two creeks (Borrego and Serrano). In the map, the Great Park is illustrated in light orange, and future development is yellow. This reach of the corridor is on deed-restricted land owned by the City of Irvine and will be constructed by Five Point Communities.

Southern Reach: South of a difficult crossing under the enormous I-5 freeway, the southern reach of the corridor follows existing green channels through The Irvine Company’s Spectrum 5 research park in Irvine. It continues coastward along Needlegrass Creek (Veeh Creek) and ultimately enters the protected parklands of Laguna Coast Wilderness Park.

Challenges Ahead

Design and engineering solutions are needed along the corridor to make sure wildlife can pass under, over, into and out of several obstacles: roadways, creek channels, and railroad tracks. The corridor also needs to be properly buffered from development along its flanks: too much noise or light, and any intrusion of people and their pets, will make wild animals and birds less likely to use the corridor.

The corridor coalition is working to meet these challenges, while also seeking support for additional scientific studies to determine how wildlife are using the corridor and to learn where improvements may be needed.

NORTHERN REACH

The foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains lie just beyond this FBI-managed property that is part of the Nature Reserve of Orange County.

Status

Believed to be functional, but analysis of fencing and culverts is needed to confirm that wildlife can pass through. Potentially threatened by development proposed on County property.

Description

The Northern Reach of the wildlife corridor begins at the Irvine Boulevard/Magazine Road undercrossing. It is called the Alton Wildlife Movement Corridor where it passes through a County-owned property before reaching a 900-acre parcel of open space currently managed by the FBI. At the northern edge of the parcel, wildlife can reach Limestone-Whiting Wilderness Park by using culverts beneath the 241 Tollroad—and go on to access much larger habitat lands in the Santa Ana Mountains.

Importance

The FBI-managed natural area has the highest density of Coastal California Gnatcatchers in Orange County. These birds are federally listed as ‘threatened’, having lost much of their habitat to development. This property was set aside for habitat as part of the 38,000-acre Nature Reserve of Orange County. The wildlife corridor will finally link the northern or ‘central’ and southern or ’coastal’ halves of the Reserve.

Progress

- The U.S. government repurposed the 900-acre FBI property (former FAA property) for habitat conservation in 1996, when Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt came to Irvine for the signing of a unique contract (Natural Community Conservation Plan, or NCCP) between the U.S. Government, California, Orange County, The Irvine Company, and other public and private landowners. This agreement created the Nature Reserve of Orange County.

- Despite earlier concerns about the expansion of FBI training facilities on the reserve land, wildlife movement appears to be continuing through the site. The habitat has rebounded since the 2007 Santiago Fire.

- When the 241 Tollroad was constructed, four undercrossings adjacent to the FBI property for water and animals were included in the design. The largest one is at the northwest corner of the FBI property, where Agua Chinon Creek crosses under the tollroad. Monitoring studies have shown that larger carnivore animals use the Agua Chinon undercrossing, and smaller animals probably use the others as well.

- In 2012, the Alton Wildlife Movement Corridor was completed on an approximately 44-acre parcel now owned by the County, as mitigation for extending Alton Parkway through important habitat lands and impacting Borrego Wash.

- In 2014, the County of Orange issued a The West Alton Development Plan Notice of Preparation (NOP) and proposed to build 70-unit multifamily housing development on the 44-acre western County parcel. This project could have negatively impacted the corridor function by introducing light, noise, and human/pet intrusion into the corridor. On February 6, 2020, a California Superior Court ruled against Orange County on their development plans for two projects known as the “100-acre parcel” and the “West Alton parcel.” Both projects are located in Irvine and would have impacted the Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor The Laguna Greenbelt partnered with several other entities in this litigation. The Court ruled that the County of Orange must seek approvasl from the City of Irvine for both projects. The EIRs for both projects can not be used for any future development. Then, on June 23, 2020, the County of Orange rescinded the approvals and all associated documentation for both projects. Because of LGB Inc. and its partners involvement in this legal case, the proposed projects will no longer move forward. Essentially, any future developments will start at square one again to go through the public process of acquiring permits, etc.

Challenges

- Wildlife movement may be impeded by fencing between the County and FBI properties, as well as debris in the smaller culverts under the 241 Tollroad. An analysis of ground conditions is needed now, as well as monitoring and maintenance in the long term.

- Also in the NOP referenced above, a map designates the ‘East Alton’ County parcel, adjacent to the wildlife corridor and part of the Nature Reserve of Orange County, for agricultural use. The East Alton parcel is designated as ‘critical habitat’ for the coastal California Gnatcatcher by the Federal government, and along with the FBI parcel, contains the highest density of gnatcatchers in Orange County. Further information is needed about the County’s intentions for this property, if any. City of Irvine zoning also designates the parcel as Exclusive Agriculture rather than Preservation.

CENTRAL REACH

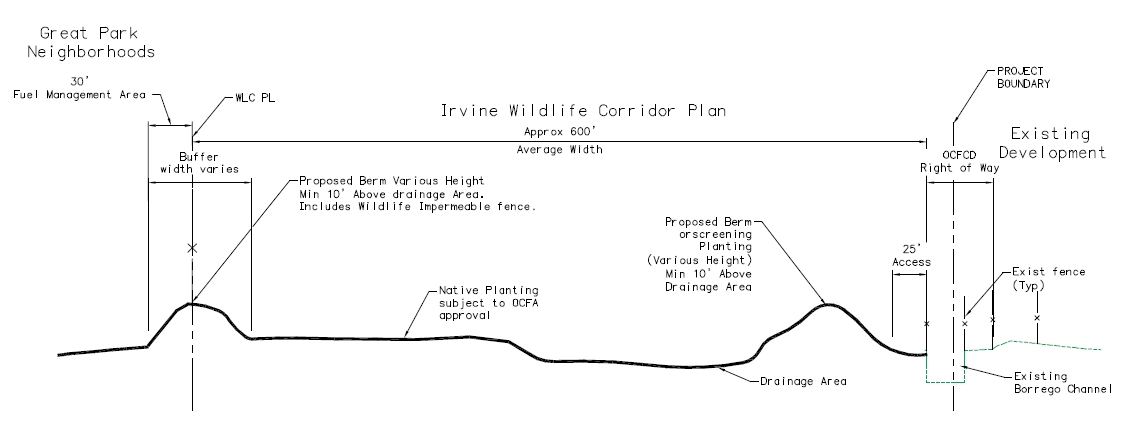

North of the I-5, the corridor emerges in the Serrano Creek bed where new upland habitat parallel to the creek is already available to wildlife. The corridor crosses under the Alton/Culver intersection, and climbs into a wide landscape bordered to the North by railroad tracks. Wildlife-friendly fencing allows for crossing the tracks. It will cross over the Borrego Creek channel on wildlife bridges and continue northward, with the channel and existing industrial development on its east side, and planned Great Park Neighborhoods to its west. High berms and vegetation will screen wildlife from neighboring developed areas. Fences on either side will keep wildlife in the corridor and human/pet intruders out. (See diagram below.) Plantings will include southern cactus scrub, coastal sage scrub, and riparian scrub. The width of the corridor in this Central Reach varies from 440 feet to 1,100 feet.

This typical cross-section shows the combination of planting, drainage, and berms that are planned for the corridor in the Central Reach, north of the Borrego Creek crossing.

Importance

Importance

The development of the Great Park Neighborhoods on the former MCAS El Toro base provides an unprecedented opportunity to create a wildlife corridor that connects the Laguna coast and Santa Ana Mountain wildlands. Specifically, this alignment provides a direct connection between the northern and southern halves of the Nature Reserve of Orange County.

Progress

- Five Point Communities—the developer for the Great Park Neighborhoods—and the corridor coalition have negotiated and agreed on a consensus plan for constructing the corridor. This plan was informed by wildlife movement experts who were convened at a 2012 workshop, and it was endorsed by federal and state wildlife agencies. This video shows restoration biologist Tony Bomkamp telling the story of that collaboration.

- The consensus Irvine Wildlife Corridor Plan was adopted by the Irvine City Council in late 2013. The corridor is now reflected in the city’s general plan and zoning. Land swaps in early 2015 placed the corridor land under City of Irvine ownership, with a deed restriction limiting it to wildlife corridor use only.

- Five Point Communities has agreed to finance and carry out construction of the corridor as a feature on the edge of the Great Park Neighborhoods. Construction is anticipated to begin in 2018, with completion expected in 18 months.

- Looking ahead to the future planting work, Five Point Communities has established a cactus nursery using pads harvested from local cactus patches. These plants are being used to grow a stock of local cactus for the future cactus scrub habitat in the corridor.

Local prickly pear and cholla cactus are being grown for the future wildlife corridor in a cactus nursery, shown here soon after cactus pads were transplanted from a nearby site (without harming the donor plants!).

Challenges

- The corridor has already been designed to overcome several man-made obstacles. It will include an access ramp for the Serrano Creek channel and two vegetated covers (wildlife bridges) across Borrego Creek, as well as new roadway undercrossings beneath Astor Road and a future Marine Way extension. The corridor will use the existing roadway undercrossings at the Irvine Boulevard/Magazine Road and Barranca/Alton intersections.

- Permission from OCTA and Metrolink is still needed in order to install wildlife permeable fencing near the Irvine Transportation Center, as specified in the Irvine Wildlife Corridor Plan. Current fencing presents an obstacle to wildlife crossings, and an undercrossing at this location is not feasible.

- It is important to establish a meaningful and ongoing stewardship program for the corridor that includes scientific input.

SOUTHERN REACH

Status

Currently not functional due to the under crossings at I-5 and Lake Forest Drive that are designed solely for water movement, without accommodations for wildlife.

Description

Description

The wildlife corridor in this reach is intended to follow existing creek channels through the Spectrum 5 research park, where three creeks converge. The channels for the San Diego and Serrano creeks are wide, vegetated, and screened/fenced from the surrounding development. The corridor reaches these channels by passing alongside Needlegrass Creek under the Lake Forest Drive extension to meet San Diego Creek. It follows this creek for a short distance, passes under Irvine Center Drive and Research Drive, then heads north along a vegetated swale that was built alongside the CarMax property. At the end of the swale, the corridor passes under the I-5.

The wildlife corridor in this reach is intended to follow existing creek channels through the Spectrum 5 research park, where three creeks converge. The channels for the San Diego and Serrano creeks are wide, vegetated, and screened/fenced from the surrounding development. The corridor reaches these channels by passing alongside Needlegrass Creek under the Lake Forest Drive extension to meet San Diego Creek. It follows this creek for a short distance, passes under Irvine Center Drive and Research Drive, then heads north along a vegetated swale that was built alongside the CarMax property. At the end of the swale, the corridor passes under the I-5.

Importance

Creeks in the Spectrum 5 research park area provide a natural—and crucial—connection between coastal preserve lands and the Central Reach of the wildlife corridor. The creek channels are suited for wildlife corridor use, and most surrounding land uses are good neighbors for wildlife.

Progress

- Channels for the San Diego and Serrano creeks are wide and vegetated, providing for wildlife movement. Adjacent properties have fences and screening

—

vegetation where they abut the channels.

- Wildlife movement is technically possible under Irvine Center Drive and the I-5 freeway, but uncertain (see Challenges below).

Challenges

- The Serrano Creek I-5 culvert needs to function as part of the wildlife corridor but is too long, dark, and flood-prone. This culvert passes beneath Bake Parkway, the Bake Parkway southbound onramp, and the I-5 before finally emerging again. It is too long for animals to see daylight on the other side, so they do not perceive it as a passageway. Water in the culvert can make it impassible. Concrete benches 1-2’ tall on one or both sides would enable bobcats and coyotes to cross during low water. Other engineering solutions are needed to allow daylight to penetrate into the passageway.

For wildlife and people, passing through the I-5 culvert is currently only possible when there is no water. Concrete benches would enable bobcats and coyotes to cross during low water. The long culvert also needs to be illuminated with enough natural light for animals to perceive it as a passageway.

- The Lake Forest Drive overpass for Needlegrass Creek was not designed with wildlife passage in mind. However, when water levels are low, animals may be able to pass through.

- This segment of the wildlife corridor is not reflected on the City of Irvine zoning map. North of the I-5, the corridor is designated for Preservation, but south of the I-5 the zoning is industrial and residential. Zoning would help ensure that the corridor is properly buffered from light, noise, and intrusion from adjacent properties.

The Lake Forest Drive extension made this section along Needlegrass Creek difficult for animal passage, especially when water levels are higher. Note the standing water even in a dry period.

Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor