As Orange County has developed,

Click to visit:

Cactus wrens in the Greenbelt are struggling and need habitat to connect them to their nearby relatives in Orange County.

Fortunately, a possible wilderness linkage has been found. The Laguna Greenbelt, Inc. is leading a coalition to pursue the creation of a Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor that would allow the movement of wildlife between our 22,000-acre Greenbelt and the more than 150,000 acres of natural land in the Cleveland National Forest and Santa Ana Mountain foothills.

The Coast to Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor is designed especially to assist bobcats, coyotes, and two birds that are struggling to rebuild healthy populations: the California Gnatcatcher, and Least Bell’s Vireo.

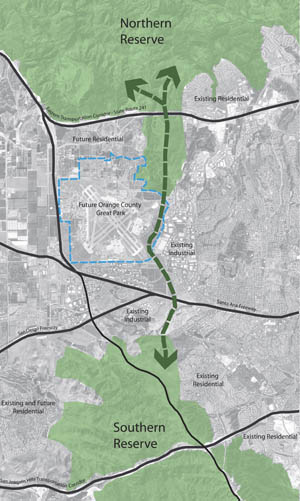

Linking the Coast to the Mountains

The Coast to Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor is envisioned as a wide, winding strip of native vegetation that roughly follows sections of San Diego, Serrano and Borrego Creeks for about 5 miles. It begins the journey from Laguna Coast Wilderness Park by following existing green channels through the Spectrum 5 research park north of Lake Forest Drive. The corridor soon makes a challenging pass under the enormous I-5 freeway at Bake Pkwy. It emerges along Serrano Creek, then crosses railroad tracks and channels to follow Borrego Creek, running along the east side of the Great Park Neighborhoods. After passing under Irvine Blvd and through County properties, it follows the creek to a large parcel managed by the FBI. From there, wildlife can reach Limestone Canyon and Whiting Ranch wilderness parks by passing under the 241 Tollroad—and go on to access much larger habitat lands in the Santa Ana Mountains.

A major victory came in 2013 for the central portion of the corridor along the east side of the Great Park Neighborhoods. That year saw the City of Irvine—which owns this stretch of the corridor—adopt a corridor plan that the coalition had negotiated with developer Five Point Communities, with input from wildlife movement experts. Five Point Communities is poised to invest $13 million in the successful implementation of this central portion of the corridor, including planting/landscaping and the construction of under/overcrossings as well as a tall berm to screen the corridor from development. Construction is expected to begin no later than early 2018, and take 18 months to complete.

Other progress on the corridor includes the County’s creation of the Alton wildlife movement corridor north of Irvine Blvd, connecting the Great Park section to the FBI-managed natural lands; and the system of undercrossings along the 241 Tollroad that allow wildlife to safely pass under this boundary.

Challenges

Design and engineering solutions are needed along the corridor to make sure wildlife can pass under, over, into and out of several obstacles: roadways, creek channels, and railroad tracks.

The corridor also needs to be properly buffered from development along its flanks. Too much noise, light, and the intrusion of people and their pets will make wild animals and birds less likely to use the corridor.

The corridor coalition is working to meet these challenges, while also seeking support for additional scientific studies to observe how wildlife are using the corridor and learn where improvements may be needed.